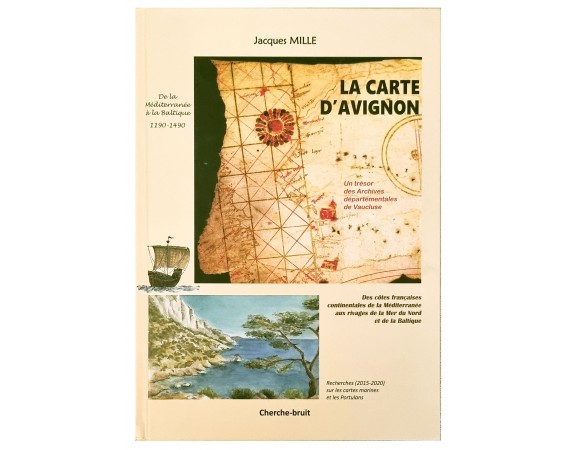

La carte d'Avignon: De la Méditerranée à la Baltique 1190-1490

Click on image to zoom

Click on image to zoom

Description

The Carte d’Avignon is a celebration of research by a highly enthusiastic amateur who has put a great deal of time, energy, and rigor into the investigation of a newly discovered portolan chart. Jacques Mille is a member of the Brussels Map Circle, and his fellow members can only applaud the detail of the work undertaken. He is also an expert in communication, having brought on board experts such as Tony Campbell and Ramon Pujades i Bataller, whose experience in the field of marine charts has clearly helped to narrow down the possible identity of the chart. The book is divided into three parts. Part One (2015-2017) describes the author’s initial passion for maps and how he published books on old maps of the Alps and of the Calanques, the coastal area near Marseille 1 . A meeting with Tony Campbell led to further research into toponyms and other aspects of the coasts of Provence on old maps, this in turn leading to his presentation at the Lisbon conference (on the Origin and evolution of Portulan Charts) in June 2016.

The author says that he imagined that his research 1 See review in Maps in History No 55. 2 See report in Maps in History No 56 would end there; however, it was just about to take off! His research led him to a PhD thesis by Paul Fermon, in which there was an illustration of a marine chart that reminded him of the Carte Pisane. Paul Fermon gave Jacques a free hand to start on a journey of discovery, as he did not feel it was of direct interest to his own work. The author’s initial research centers on the French coast from Spain to Italy, a tiny part of the Mediterranean coast as a whole, but an area that he already knew well.

Jacques analyzed the information found in the Carte Pisane, the Cortona chart, and the Lucca Chart, together with Pietro Vesconte’s Chart (1313), which was the one that became the model for charts up to the seventeenth century. In particular he dissects the shapes of the étangs – salt lakes – and the Rhone delta and the toponyms of the area.

His analysis is beautifully – and usefully – illustrated, leaving the reader in no doubt about his points, and making the reading most pleasurable. Jacques also makes use of two ‘portolan texts’, written in the form of nautical instructions: Lo Compasso de navigare, and the Liber de existencia riveriarum et forma maris nostril mediterranei, plus three other texts: De Viis Maris, describing a voyage from England to the Holy Land, the Compass book – a translation of a fourteenth century Catalan ordinance, and the Rizzo portolan, per tutti i navichanti.

Part One finishes with an overview of the evolution of the mapping of the Mediterranean coast from the earliest known charts to the seventeenth century

Part Two (2017-2018) moves on to the research into the Avignon Chart itself. It is a fragment of a manuscript marine chart that was discovered in the archives of the Vaucluse in Avignon. As described above, Jacques Mille came across it in the thesis of Paul Fermon. Unnamed and undated, initial studies indicated that it might date from the beginning of the fourteenth century.

Further interest stemmed from the fact that it showed the eastern coast of Great Britain, plus the northwestern coasts up past Bruges to what is now western Latvia. Early portolan charts are very rare, so despite the parchment being in poor condition, with the eastern part cut off, and the surviving part very damaged, it was still very well worthwhile studying and putting in the context of the well-known charts of the era. The Chart was restored in 2003. The author pays particular attention to the Languedoc coastline — part of France’s Mediterranean coast, and the Gulf of Gabès in Tunisia (Fig. 1). As before, comparisons are made with known old portolan charts, i.e. the Carte Pisane, the Cortona and Lucca charts and Vesconte’s 1311 and 1313 charts.

As regards the approach to dating: ‘A dating approach thus leads us to placing the Avignon Chart around 1300-1310, among the oldest surviving charts, possibly in the third position after the Carte Pisane and Cortona Chart, but before the undated and anonymous Riccardiana Chart, and the signed and dated charts of Pietro Vesconte 1311 – 1313 as well as the later charts of Carignano and Dulcert (1327, 1339 respectively). 4 There are some special features on the Chart, not least the coloured twenty-four petalled flower, and seven carefully-drawn churches all outside the Mediterranean area. These may be the first ever non-nautical drawings on a nautical chart. As regards the construction of the chart, the author 4 Quotes in English are taken from the English abstracts at the end of the book points out that there are two distinct spaces on the existing part of the chart: first, the Mediterranean part which is drawn in a more or less traditional manner, the second the areas beyond, ‘with coasts drawn correctly for France and England but in an aberrant manner, and schematic in their orientation, for those beyond Bruges’.

One of the author’s favorite analytical tools is the study of toponyms, and he gives the reader a detailed but very digestible table comparing many of them, also including the Liber and the Compasso in the comparison. The drawing of the sector beyond Bruges indicates that the mapmaker probably had to work based on hearsay, and leads the author to describe the voyages of the Genoese traders to the north of Europe, and in particular their presence in London and Bruges. Mariners would journey from the Baltic and inform those trading further south. Jacques illustrates in detail the various goods traded with the north, and how the Hanseatic ports forbade those from the Mediterranean to trade there. Part Two ends with the rationale for the Chart being in Avignon. The town was the Pope’s residence from 1309, and so it became the center of Christianity and, at the same time, a major commercial hub.

As a consequence the Genoese were there in large numbers. Part Three (2018-2020) deals with Jacques’s later, and latest, research, mainly into the non-Mediterranean sector, i.e. that covering the North Sea area, including the German coasts, the Danish peninsula and the southern shores of the Baltic Sea. His research built on the ‘hearsay’ theory described in Part Two and describes the ‘decisive turning point’ in 1320-1330 with charts drawn by Pietro Vesconte in Marino Sanudo’s document presented to Pope John XXII advocating a new Crusade. These charts, together with those of Carignano and Dulcert, came to be recognized as the first to represent these northern regions, although with very different levels of accuracy. The author mentions, for example, that Dulcert clearly had good knowledge of the cities of the region, but did not place them on his chart accurately. Given these comparisons, he states that there are two views on the dating of the Avignon Chart: first, preVesconte (i.e. 1300-1310) and second, contemporary or post-Vesconte. He makes comparisons of the drawing of the coast of England, the French Atlantic coast and the Danish peninsula and the Baltic Sea to try and support his theory of pre-Vesconte, 1300-1310. Jacques’s view, as stated above regarding his dating approach, is that the Avignon Chart is the third oldest – after the Carte Pisane and the Cortona Chart... ’and the first to represent the northern regions, before Carignano and Dulcert. It would be considered pioneering, isolated and without subsequent works. [The chart was] drawn up for these northern regions on direct data for the English coasts and as far as Flanders - Holland and on indirect data for the coasts beyond Bruges, which were controlled, before being blocked, by the Hanseatic League.

But there is certainly no controversy about the fact that the chart maker was a professional working at the beginning of the fourteenth century, and probably in Liguria, i.e., the Genoa region, but away from Vesconte’s workshop. Reading the Carte d’Avignon makes you feel that you are listening to the author explaining his research, his thoughts and proposals, and his efforts to make sense of his discovery. At every moment, he illustrates his presentation with (parts of) maps, sketches, diagrams, and tables, extracts from experts, and abstracts in English. Jacques keeps the reader constantly on his/her toes and does not let up on his own views. At the same time he is grateful for the help and support from experts in the field. It is both an excellent read and a reference for those interested in how to go about researching the background to cartographic material. I find it a pity that it has a limited print run of 400, as it seems to me that its potential readership is all those amateurs who are interested in the field but who do not know where to start, rather than the cartography ‘lifers’ who will have undertaken the process many times.

- Reference N°: 48808